How do the EU forest guidelines impact the Forest Industry?

Forests are among the cornerstones in combating climate change and preserving biodiversity. The European Union has drawn new guidelines and set ambitious targets to ensure the sustainability of forestry activities. Despite being part of the same economical regime, the European countries differ in terms of economy, industry structure and wildlife habitats and national differences must be taken into account in decision-making.

Forests amidst regulations

The EU’s New Forest Strategy for 2030 sets out the Commissions’ objectives for forests and the path forward to reach the targets of the Green Deal. The three main platforms steering the use of forest assets in sustainable manner are RED III, EU taxonomy and LULUCF.

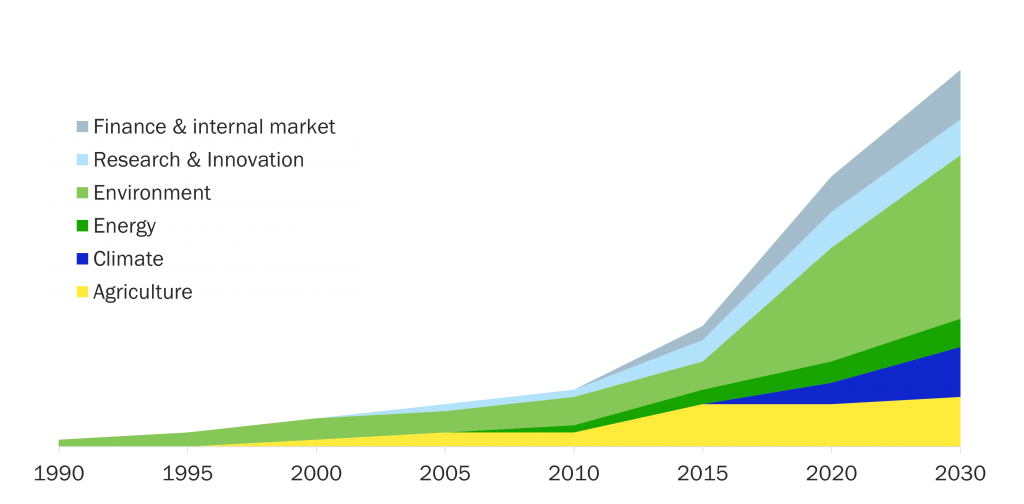

The regulation within EU is rapidly increasing up to 2030 to meet the ambitious targets of the European Green Deal. Source: Vision Hunters, public sources

The revisited Renewable Energy Directive, RED III, aims to increase the EU’s emission reduction target from current 40% to at least 55%. Several proposals have also been made to change the sustainability criteria for forest biomass. In the future, forest biomass harvested from certain no-go areas, such as primeval forests, would not be classified sustainable. Bioenergy production and incineration of processable wood would no longer be supported. In addition, Member states should also ensure that adverse market and biodiversity impacts of bioenergy production are minimised.

The Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) covers human activities resulting in emissions in agricultural land, forested land, wetland, or peat. It is meant to provide a framework for more targeted policies at national level.

In relation to forestry, EU taxonomy for sustainable actions is a classification system establishing a list of environmentally sustainable forest management actions. In implementing the forest strategy, the taxonomy is meant to establish a common language and measures. It is aimed to take a stand for water protection zones, quantities for decaying wood and the restrictions for clear cuttings. The linkage between forest strategy and taxonomy is not crystal clear for all and needs more specifications in the future.

One size does not fit all

The aim of the New EU Forest Strategy for 2030 is to ensure that Europe’s forest ecosystems are resilient and diverse. However, the strategy has raised concerns within the forest industry, since the strategy is said to take too much stand on matters of national quorum. There are 27 member states in EU with unique forests and habitats and a too uniform approach may hamper the EU’s proximity principle, where the decisions are made as close as possible to the country of destination.

Secondly, the forest strategy seems to place too much emphasis on conservation measures while neglecting the social and economic dimensions of forests. The overall sustainability is achieved only if the revenue streams of forests and their social importance are accounted for. As forest assets are a part of the solution in the green transition and plastic substitution, achieving the climate targets require innovation and bioeconomy-based investments. It is criticized that this aspect is poorly recognized in the strategy.

Role of forests and forest-related investments needs vary greatly between the member states. For some nations forests are an essential part of livelihood and well-being.

The area covered by forests differs from under one fifth in Denmark, Ireland and Netherlands to over 60% in Finland and Sweden. The latter countries have a long history in forestry with strong cultural and socioeconomic aspects. Therefore, the regulations have heterogenous impacts and disproportional implications on member states’ industries.

Thirdly, the administrative and financial burden of the forest owners increases alongside the regulation. Around 60% of European forests are privately owned, but this share varies greatly between countries. Private ownership is linked to sustainability promotion. This is due to the fact that privately owned assets are typically better cared for than common property.

The legislation should stimulate sustainable forestry by granting support to forest owners, since the investments made in forest assets must pay off. In the end, it is the capital markets that have the real impact, and legislation can either support or suppress that.

The forest strategy does not seem to bear in mind that at least some forests need active management to adapt to climate change and to maintain carbon sequestration, which is at its peak among young, growing trees. Moreover, forest owners apply different practices to their forests, creating diversity and possibly increasing biodiversity.

Trumping national power of decision, the countries depending on forestry and the pulp & paper industry may face huge financial losses, which might have a detrimental impact on national income generation and well-being. There is a risk that unequal legislation or its implementation increase the tensions within the EU.

Related content: Forest and bio-based industries – a part of mitigating the global environmental chrisis

Reconciling different forest-related needs

There is an urgent need for change to ensure a habitable planet, and forest assets play significant role in this. Forest industry provides numerous fossil-free end-products many of which can be used as an alternative to plastic products.

Access to sustainably managed wood resources is vital to create value adding bio-based products.

Different forms of forest management are needed since forests are unique and different lots require different actions. The protection measures and restrictions in use should be properly targeted, since not all hectares have equal value in terms of biodiversity and financial profit.

The volume of European forests is growing. The carbon leak must be taken into account when talking about climate change. The forest industry sector in Europe is relatively sustainable when compared to many other industries, and modern biorefineries are already able to effectively utilise side-streams from the pulping processes. Legislation should support the European forest industry and its competitiveness to avoid moving the production outside of Europe, where the environmental performance may not be as good.

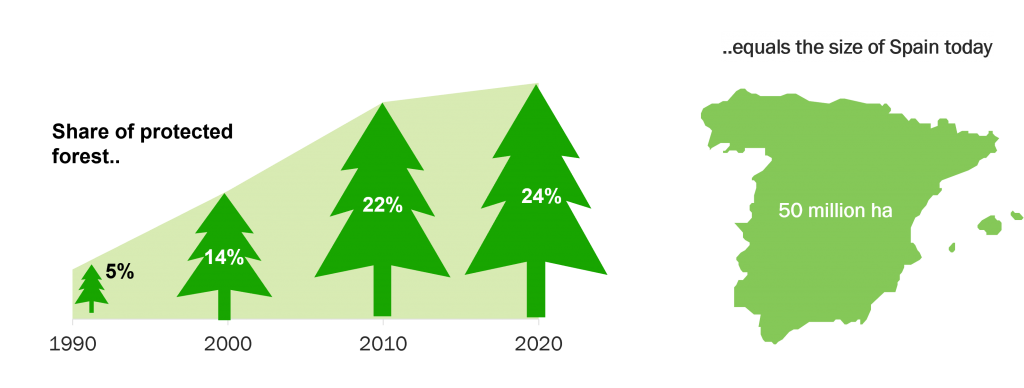

The share of protected forest area in Europe has been increasing since the 90s, totaling the size of Spain today. Source: CEPI

To reconciliate different forest-related social, economic, and ecological needs the countries need establish a proper dialogue and identify common ground in how to define goals and measures to achieve them. In close cooperation with different stakeholders, the new forest strategy is easier for individual member states to adapt and implement in a way that allows for national decision making while also acknowledging the distinctiveness of different local forest lots. One way to pursue consensus is to increase R&D exertions. It provides scientific answers and data about the states of forests and aids in finding optimal solutions for treating forests of various ages and species. Common targets with national measures are needed to reconciliate the social, financial, and ecological equation of forests.

On the author: Hanna Lahtinen, Strategy Analyst. Hanna has a Master of Science in Economics & Business Administration and has also studies in Environmental Engineering. She has experience in circular economy from the primary and secondary sectors and is keen to promote sustainable use of natural resources

Vision Hunters provides strategic advisory services for the forest and bio-based industries, and energy sectors. We assist leadership teams in making the smartest strategic choices to improve the outcome of their company in the future. We are highly experienced and result-oriented and have advised many of the leading companies in our industry.

Related content: Forest and bio-based industries – a part of mitigating the global environmental chrisis